Henrietta Lacks

May 30, 2019 in Henrietta Lacks, History of research ethics, informed consent, Research, Research ethics, respect for autonomy

In my last blog I wrote about the events reported during the Nuremberg Trial of doctors and others who undertook unethical and harmful research before and during World War II and the subsequent Nuremberg Code. It became clear during the trial that many innocent people had been forced to participate in unethical research undertaken in the name of science and that astonishing numbers of people had suffered and died as a result. In contrast, in this blog I will write about the research undertaken on tissue samples taken from a single person.

Henrietta Lacks was a poor African-American women who was born in 1920 in Virginia. In 1941 Henrietta Lacks married her cousin, Davey, and later that year the family moved to Turner Station in Maryland so that Davey could work at Bethlehem Steel. Following the birth of their fifth child in 1951, Henrietta suffered a haemorrhage and attended the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. A biopsy was taken and Henrietta was diagnosed as having a malignant cervical cancer. She was treated but died on 4th October 1951.

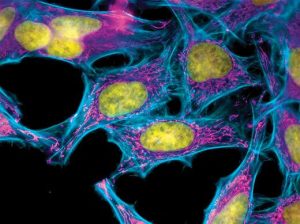

Samples taken from Henrietta Lacks were given to Dr George Otto Gey. Gey had long been attempting to culture cells in such a way that they could be used for research but they never lived more than a few days and didn’t live long enough to be used for research. Gey observed that Henrietta’s cells reproduced quickly and did not die like previous cells. The cells were given the label ‘HeLa’, which included the first two initials of Henrietta’s forename and surname. Because of the way the HeLa cells behaved, they were soon in great demand and started to be reproduced on an industrial scale so they could be sent to researchers around the world.

HeLa cells have been used in much research that has made significant contributions to medicine, including development of the polio vaccine. The extent to which the HeLa cells have been reproduced and used is almost unimaginable but it has been estimated that as much as 50 million metric tons of cells being made available for research and that there are as many as 11,000 patents involving HeLa cells (Margonelli 2010).

In the 1970s there was a controversy in which cell cultures from around the world, even from Russia, were contaminated with HeLa cells which led to misleading results until the contamination was recognised. It was at this time that members of Henrietta Lacks’ family were approached by researchers seeking samples. Until they were approached, the family had no idea that Henrietta’s cells had been collected or that they were being used in this way. At the time they were collected, informed consent was not sought, as was common practice at the time.

In 2013 researchers published the DNA sequence from a strain of the HeLa cells but Henrietta Lacks’ family only discovered this when the journalist and author Rebecca Skloot approached the family. They objected that their genetic information had been made publicly available because they did not know it was going to happen and because what this genetic information might make known about Henrietta Lacks’ descendants was unclear. This issue was finally resolved when the NIH gave the family some control over how the DNA data might be used.

In recent years there has been significantly greater recognition of Henrietta Lacks’ contribution to medical science, including an annual lecture series, having buildings names after her, being awarded an honorary doctorate by Morgan State University and even having a minor planet named after her. The story has also been told on the small and big screens. In 1997 the story was told in a BBC documentary and events around the collection and use of Henrietta Lacks’ cells was the basis for the storyline for an episode of NBC’s ‘Law and Order’. In 2017 Rebecca Skloot’s book, entitled ‘The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’, was turned into a HBO film of the same name with Oprah Winfrey in the leading role. The story has even been told on the stage with J. Nicole Brookes’ play ‘HeLa’ being staged at Chicago’s Greenhouse Theatre Centre.

The story of Henrietta Lacks and her cells has now received much public scrutiny and has contributed to discussions around the exploitation of vulnerable minority groups. The story has also received much attention from those with a professional interest in research ethics with a number of papers being published in academic journals. In both the popular and scientific press, the most interesting discussions have been around the lack of consent to initially collect and use the samples for research purposes.

Whist it was not common practice in 1951 to seek informed consent to use samples for research in this way, this doesn’t mean that informed consent shouldn’t have been obtained. In my last blog I wrote about the Nuremberg Code of 1947 in which it was made clear that informed consent should be sought for research involving human participants. Dr Gey’s actions in trying to hide the source of the samples, initially indicating that they came from a patient called Helen Lane, also suggests that ‘common practice’ might not have been considered the most appropriate practice, even by those engaging in it.

If Henrietta Lacks were a patient now, her samples would undoubtedly not have been used in this way without appropriate informed consent being in place. It would also have been necessary to seek a favourable ethical opinion from an appropriate Research Ethics Committee to use tissue samples for research. In addition, in the UK the 2014 Human Tissue Act places particular requirements on researchers when collecting and using human tissue for research or when storing that tissue for future use.

Henrietta Lacks’ cells, in vast quantities, have contributed much to medical research since they were first collected in 1951. It is, however, regrettable that the samples were collected and used for research without seeking informed consent from Henrietta Lacks or her family. There might not have been any physical harm caused to Henrietta Lacks, or her family, but the fundamental ethical principle of autonomy has not been respected. There may be occasions when seeking informed consent might be impractical but this does not appear to have been the case with Henrietta Lacks.

In this blog I have described one of the best known examples of respect for autonomy being neglected. In my next blog I’ll explore how obtaining informed consent does not always mean that research participants are informed and where, as a consequence, participants are harmed.

Further Reading:

If you would like to know more about Henrietta Lacks and her family, I strongly recommend reading Rebecca Skloot’s fascinating book ‘The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’.

← The Nuremberg Code (1947) False Starts, Flexibility & Persistence →

Leave a Reply